(Reading Time: 4 minutes)

Why counting clocks and keystrokes won’t stop time cheats

It was a problem even before Covid sent everyone working from home: how to make sure your employees are working the hours that you pay them to work.

There are the mundane, daily stories: people routinely showing up at 9:10 a.m. when their start time is 9:00 a.m., co-workers taking 70 minutes instead of 60 for lunch, or that one person who always leaves 15 minutes before 5 p.m. to catch the early train home.

There are the mundane, daily stories: people routinely showing up at 9:10 a.m. when their start time is 9:00 a.m., co-workers taking 70 minutes instead of 60 for lunch, or that one person who always leaves 15 minutes before 5 p.m. to catch the early train home.

Then there are the crazy cases that you hear about on the news. Someone in Europe who was missing for years but still getting paid. Another person who had two full-time jobs: working two days at one and three at the other but claiming five days at both.

Of course, stealing minutes from your employer is nothing new.

One of my first jobs as a student was at a Goodyear tire factory in Etobicoke. We had to punch in and punch out, and there were all kinds of cheating, even then. Some people would leave early and have a friend punch them out along with their own card. Conversely, you’d have someone punch you in if you knew you would be late.

Of course, even if you punched in and out at the appropriate time, it didn’t mean you were working hard. Management found one guy on the night shift, for example, who had built a bed in the back of the warehouse, and he would sleep there during his shift.

I’m also mystified by the complicated jokes and memes that circulate online. Someone has put a lot of time and effort into creating them. Did they create them at their cubical in between online shopping and maybe logging a bit of actual work?

But who’s to blame for these time cheats? To me, ultimately, when things go wrong, it’s the boss’s fault. No matter what it is. Even—or especially—in this case.

Maybe your procedures weren’t detailed enough to catch what was going on, like someone working only two days a week but claiming five. Or your training wasn’t enough, or your screening wasn’t the right screening to get the right people in the first place.

(There will always be exceptions. One person will get through your screening, ignore your procedures, try to get around your rules and lie and steal. Eventually, you’ll find out, and then you’ll have to deal with them. But it should be fairly minimal if you have done everything else.)

So, what’s the solution?

I think the best defense is a good offence when you:

- hire the right people

- build trust

- communicate expectations

- focus on output and results.

Hire the right people

Hiring the right people in the first place is the best defense. Hire for compatible values, enthusiasm, and your best guess at their trustworthiness.

When you’re considering a candidate, having the right skills and experience is important but it is absolutely critical that they have the right personality and work ethic. When checking references, ask if this is a candidate who will go the extra mile or jump up to leave at exactly 5 p.m. Did they consistently meet deadlines or consistently deliver excuses?

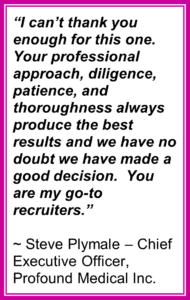

The Kathbern team all work remotely and part of their compensation is on an hourly basis. However, success is very measurable—either they successfully filled a role, or they didn’t. Nevertheless, a significant portion of compensation is based on hours, which are voluntarily reported weekly. I have never questioned anybody’s hours, ever, and I’m talking years here.

But, I have a general idea of how many hours it should take to get a job done. I know that each job is different, and they all have challenges, and there are a million reasons why things go sideways…but I would eventually have an indication if I was being overbilled.

If someone slips in an extra hour or two, I’m not going to know. But in the longer term, that individual will be comparatively expensive, because it’s always taking them a lot of hours to get something done, whereas somebody else seems to get it done in fewer hours.

So, I’ll start offering less work to that person. And that will shimmy things up again for what’s fair and not fair. That’s why you want to have trust, but you also want to be able to measure the hours against some sort of baseline.

Trust…but verify

If we go back to the case of the person who was missing but getting paid—where was their employer? Did they not notice they had someone on their payroll who wasn’t sitting at their desk? Even if they worked totally remotely, was there no accountability for results?

Trust can’t be blindly given; it has to be earned. You hire people that you hope you can trust out of the gate, and then check frequently in the early days. Make sure everything seems good, and that they have earned that trust. As time goes on, you can check less.

You don’t want to be monitoring your employees all day, but you should have a sense of how long it will take to complete certain tasks, and what a reasonable person should be able to complete in a given time frame.

This will be easier in some cases than others. If you have more than one person doing the same task, you’ll have some comparisons.

Whereas if you’re managing an individual contributor, and they’re the only one, it can be hard to do. Especially if they are doing a job that you have never done yourself. But there will be hints—do they have a sense of responsibility about staying on top of their work…do they sometimes work overtime or come in on a Saturday to catch up?

That’s why, once you’ve hired the right people, as best you can, it’s about managing what their output should be compared to what output they are actually giving you.

Communicate with your team

What if the output you’re getting isn’t what you expect?

It doesn’t necessarily mean that you have a time thief on your hands. It could mean that your expectations aren’t realistic. That’s why it’s so important to communicate your expectations with your employee and ask for their feedback, particularly if it’s for a job that you’ve never done before.

It could also mean that your employee is doing more to complete the task than you were expecting, or that they need additional training, or that they are focusing on the wrong thing.

Sometimes an incentive system can work well in combination with hourly rates. When I worked at Goodyear, one of the jobs was testing finished tires. There were five or six machines, each manned by one person. The machine would inflate the tires and spin as if it were on the road, then draw a little graph to show whether it was an even surface or had a lot of lumps in it.

Sometimes an incentive system can work well in combination with hourly rates. When I worked at Goodyear, one of the jobs was testing finished tires. There were five or six machines, each manned by one person. The machine would inflate the tires and spin as if it were on the road, then draw a little graph to show whether it was an even surface or had a lot of lumps in it.

These guys would run these tires through at a nice leisurely pace until management decided to base their pay on an hourly rate plus an incentive of a certain number of cents per tire. Suddenly, output was doubled. And they were making a fortune. (Naturally, after two weeks, management cut their rate in half.)

So, you have to be clear about your expectations and what’s reasonable. Ask your employee how long they think the task should take. Have a conversation. They could give you an unrealistically long timeframe, but at least it sets a benchmark.

Focus on the output

At the end of the day, the most important thing is the output of someone’s work (quality and quantity).

If you’re a machine operator at the tire plant, we can measure how many tires you make in a day. That’s an important measure. But it’s not the only measure—it’s no good if you’re producing a bunch of tires quickly that are unsafe.

Or think about a customer service call centre. In a big company, you’ll have a large pool of hundreds of people taking calls, and everything can be measured: how many calls each person takes, how long the call was, etc.

But focusing on the number of calls, isn’t the whole picture. An agent might take longer on a call but resolve a big issue. If an agent disconnects a call before a customer is finished, they’ll be getting through a lot of calls, but that doesn’t mean they are providing good customer service. You would be measuring the wrong thing.

To go back to time, it might make sense to look at a person’s work product over the course of three months, six months, or even a year. You should have an appreciation for a month’s work or a year’s work.

In some cases, people are moving away from the hourly rate and toward a more value-based fee. In that scenario, the focus is on the work product, not the number of hours it took to produce the work.

Think about a tax lawyer that spends 100 hours to save a client a fortune in taxes. The fee for the 100 hours will be a minuscule amount of what was saved. Some might bill them a percentage of the value saved instead.

That’s why statistics are a part of the puzzle, but not the whole puzzle. It’s not just about whether the job is done, but whether the job is done well. Because at the end of the day, what we want is the product of someone’s effort and their attention to quality.

Larry Smith is the founder and president of Kathbern Management, an executive search firm based in Toronto. Kathbern helps companies find the executives and senior managers who not only have the experience and credentials to fulfill their responsibilities, but also have the emotional and “fit” requirements that will enable them to be successful in a particular environment. Kathbern simplifies the process and, through deep research, brings more and better candidates forward than would ever be possible through a do-it-yourself passive advertising campaign.

Learn more at www.kathbern.com, or contact us today for a free consultation about your key person search. Follow us on LinkedIn, Facebook, and Twitter.